Shapes and Forms

Carved black turtle with inlaid turquoise and sgraffito flower, butterfly and geometric designs

by Melony Gutierrez, Santa Clara

3.5 in H by 6.5 in Dia

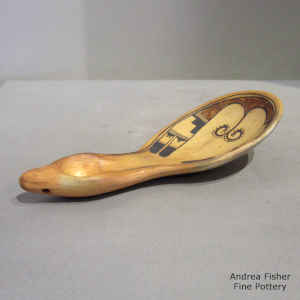

Polychrome jar decorated with black and white geometric designs

by Lisa Holt and Harlan Reano, Cochiti/Santo Domingo

9.75 in H by 9.5 in Dia

Gunmetal black bear with a sienna stripe and sgraffito heart line

by Tony Da, San Ildefonso

3.5 in H by 5.75 in Dia

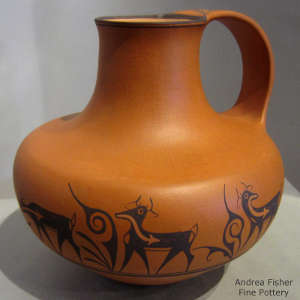

Orange water pitcher decorated with a deer-with-heart-line and geometric design

by Anderson Peynetsa, Zuni

7.75 in H by 8.25 in Dia

Shapes and Forms

Pottery comes in many shapes and forms. Some is utilitarian and some ceremonial but most is meant to be art these days. In some areas, shapes are limited by the local religion. In other areas, anything goes. And there's room for a lot of innovation in between... that's how storytellers and nativities came about. It's how seedpots (a form once purely utilitarian and now purely art) have been stretched, blown up, flattened and turned into precise geometric shapes.

There is speculation that pottery evolved from baskets, from folks pressing wet clay into the bottom of their reed baskets and then burning the baskets to harden the clay. Archaeologists have found plenty of evidence to back up that idea. And many basketmakers still put clay in the bottom of their baskets. Now we see potters making hard pottery and weaving basket materials into it.

I've seen spoons, ladles, ashtrays, salt and pepper shakers, bookends and all kinds of fantastical creatures made of clay. What I haven't seen is ceremonial pottery and that's as it should be: the Clay Mother is sacred. Even among tribes where the making of traditional pottery has almost died out there are potters making ceremonial pottery. Ceremonial pottery isn't necessarily of a different shape as much as it's about the designs on the pieces. And ceremonial pottery is shattered at the end of the ceremony, new pottery has to be made for the next ceremony.

In order to keep up with innovations in the greater marketplace, pueblo potters have to know their clay. And many potters are actively experimenting with it to see what else can be done, what else can be made. It's always interesting to talk with the more innovative potters to see where they are now. It's almost like they get out of bed in the morning thinking, "What can I do with Clay Mother today?"

Who knew that micaceous clay would make a pot that was naturally sealed and could be used for cooking directly on the fire? Who knew that mixing various colors of clay together would make a finished product that looks like a wood carving? Who figured out that smothering the fire with manure at the right time would turn the pots black? And who figured out that reheating portions of a black piece would turn them red again?

There was a time 500 years ago when Tewa and Zuni potters were producing lead glazed pottery. It was so popular that pieces of it have been found as far west as the Pacific shore and as far east as the Mississippi floodplain. Shapes and designs that seem to have been popular 1,000 years ago are still being made in some areas. Some shapes seem almost alien to me, but when I think about it, that fat tire around the middle of a Zuni pot is there to make it easy to hold onto without handles. That raised lip on a bowl is there so one could drink directly from the bowl and spill nothing. Those animal figure handles, those may be prayers for a good hunt. That animal or bird effigy is about honoring the creature it represents. Pretty much everything about traditional Native American pottery is the expression of a prayer... even when it passes into the marketplace and brings money home.

Shapes changed after the Spanish contact. Spanish settlers were used to other types of pottery and utensils. Pueblo potters were pushed to keep up with the demand, and to learn how to make those new shapes. They were pushed really hard again when the American railroads came into the area and big time traders arrived.

In some pueblos, the traders could influence the pottery only through their buying strategies. In other pueblos, what a particular trader said was "the Word of God." And there was everything in between. A particularly egregious case of this happened at Tesuque Pueblo and involved a trader named Jake Gold.

Gold saw the potters of Tesuque creating clay figures and decided to make a design that was uniquely his. He invented the "Tesuque Rain God." The Rain God was always a man sitting with a pot in his lap. There were other embellishments on some and nearly all were painted in one way or another. Some were slipped with micaceous clay, some painted with poster paints. Gold sold the Tesuque potters on his project and over a couple decades, he ordered Rain Gods by the barrel. His sales pitch in the outside world was so good he kept coming back for more, and pressing the potters to do more. But the more they did, the lower the quality fell and the less money they made. At a certain point, everyone was burned out and pottery production at Tesuque ground to a halt. It hasn't really been resumed.

At Hopi there was Thomas Keam. He set up his trading post in Keams Canyon and put out word that he was buying pottery. When potters came in, he inspected their wares, then gave them suggestions as to what he was really looking for. In that way, he was able to steer the flow of Hopi pottery making into the ancient shapes and designs of Sikyátki and Awatovi, before the archaeologists arrived and removed all the pottery they could find at Sikyátki and Awatovi, even the broken pieces.

At the same time at Hopi there were other "collectors" traveling through and buying everything they could lay their hands on, especially pots dug up in the ancient ruins. When the archaeologists arrived, they pretty much completed the plundering of a couple thousand years of Hopi civilization.

In many pueblos, the collectors and archaeologists made off with so much of the people's pottery that the people had nothing left to base their "traditions" on.

At San Juan/Ohkay Owingeh someone was excavating in preparation to build a house and they came across an abandoned ruin of the Ohkay Owingeh people. Further digging and analysis dated the ruin as having been abandoned previous to first contact with the Spanish. Pottery sherds found indicated a date around 1450-1500 CE. A couple years later several women from Ohkay Owingeh got together and decided to revive the Ohkay Owingeh pottery tradition. Because those pot sherds were from just previous to first contact, those forms and designs are what they defined their modern Ohkay Owingeh tradition on. They called it Potsuwi'i, after the village it was discovered in.

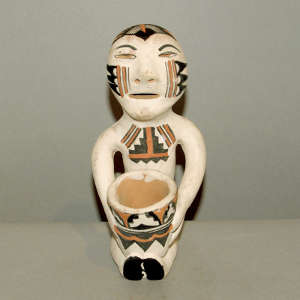

Black female storyteller with one child and a plate

by Linda Askan, Santa Clara

4 in H by 4.5 in Dia

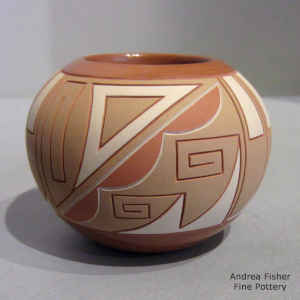

Polychrome jar with a Potsuwi'i color palette and lightly carved and painted geometric design,

by Alvin Curran, Ohkay Owingeh

2.75 in H by 3.5 in Dia

Lidded polychrome pyramid decorated with Mimbres bird and geometric designs

by Charmae Natseway, Acoma

6 in H by 5.5 in Dia