The Hopi Pueblos

Pueblo History

The southwestern people were nomads for thousands of years, moving across the countryside as the seasons and good hunting shifted. Back then it wasn't tribes or clans so much as it was family units. When agriculture was introduced, the people got more sedentary, settling into areas with good water, good soil and good hunting nearby. They began to congregate more and the first villages were established. Still, changes in the environment or other conditions would often force them to migrate to new locations and set up again.

A typical view in the area of Oraibi

- Hopituh: The Peaceful People

- Language: Hopi

- Size: 1.6 million acres

- Population: 9,000

The modern Hopi story is that the first clans came into being during their emergence into this, the Fourth World, after their passage through a sipapu from the Third World. The various clans were charged with carrying out certain rituals in order to assist the people in staying aligned with the spirits to maintain a planet that was good for the people. For instance, the Corn Clan is a seed clan, charged with carrying the seed forward through the years and providing the people with food and prosperity. The Bear Clan is the medicine clan, charged with carrying and applying the people's hard-earned knowledge of elements in their environment that were felt to be conducive for treating the people's health, both physical and spiritual. The Coyote Clan is the explorer clan, charged with seeking out, testing and adapting new and better places and paths for the people.

Changes in environmental conditions were linked to improper ritual performance, so the welfare of the people was linked directly to conservative spiritual traditions that didn't adapt well to the changing environment. There was a massive volcanic explosion at Mount Samalas in Indonesia in 1257 CE that blanketed the entire planet in ash for months. The global climate cooled, the rain came flooding down and crops failed everywhere. The pueblos in those days stored enough corn and grain to keep their residents alive for at least three years. The pueblos built in the Tsegi Canyons area had oversized storerooms built in. However, they were under attack from other pueblos and tribes who had no stores of food. When the Great Drought that began in 1276 set in, the situation got even more dire. Many disparate elements were introduced across those societies via cult and clan migrations over collapsing trade routes. Some of those elements appear to have been brought north from Mesoamerica.

There were many clans that split up and went in different directions over the next couple hundred years. The Hopi generally feel that they exist near the place where the people first emerged into this, the Fourth World, and what remains of all the clans will eventually return to their neighborhood.

Some clans that we now identify as "Hopi" have lived in the vicinity of the Colorado Plateau for more than a thousand years. Some originated in the north, some in the west, some in the south. A lot of what we now identify as "Hopi" also originated in an arc to the east: Hovenweep, Mesa Verde, Chaco Canyon, the Jemez Mountains and the Rio Grande Valley. The oral and ceramic histories of all the clans tell similar stories but each is told from a different perspective. That perspective is modified further depending on the clan relationships of the teller of the story, and by the relationships that storyteller has with any listeners.

Hopi society has been stratified into two major groups: the Motisinom and the Núutungkwisinom. The differentiation is basically around which group arrived in the area of the Hopi mesas first. Together, they comprise the Hisatsinom, the "people of long ago," who merged over the centuries and evolved modern Hopi society. The Motisinom were the people who had inhabited the mesa area continuosly for thousands of years. The Núutungkwisinom are those who came later, the first defining group coming from Paquimé in the later 1400s. The Motisinom are those who participate in the Katsina rituals while the Núutungkwisinom do not. The Motisinom clans are in charge during the Katsina season: December solstice to June solstice, while the Núutungkwisinom are in charge while the katsinas are gone for their annual summer and fall break. The Núutungkwisinom owned the rituals that bring rain, the Motisinom owned the rituals that grow corn and other crops.

The Hopi language has been built up over hundreds of years by injections of terminology from other languages. Roots of some words can be traced all across the southwestern US and northern Mexico. Same for some ritual practices and their paraphernalia. There is no distinctly "Hopi" source, only the routes of clan migrations as they came together around the Hopi mesas.

Archaeologists have traced two migrations south out of the countryside known as "Kayenta": one around 1100 CE and the other around 1200 CE. The first wasn't quite as long distance a move as the second and those migrants had a much easier time of merging into the societies they migrated to. That first migration also didn't travel with significantly better technology than the locals they settled with, like those of the second migration did.

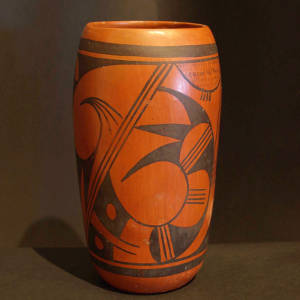

That second migration has been tracked as far south as the San Pedro River Valley in southern Arizona and Paquimé in Mexico. The biggest tell-tale of their travels is the Roosevelt Redware pottery that they made no matter where they traveled. They were able to easily adapt the clay recipe to local materials everywhere and produce a product of comparable usability and value throughout. However, in many places they settled near an earlier, indigenous population and may have merged with them over the course of several generations. Or they may not have, because there is also a trail of Roosevelt Redware headed back north to the Hopi mesas near the middle of the 1200s CE. It was shortly after that movement ended that the mass outflow of people from the Mesa Verde and Four Corners area began.

That outflow of people has been blamed on a prolonged drought that struck the area beginning around 1276 and continued for maybe 20 years. However, there was a drought in the 1100s that was significantly worse, for a longer period of time. There was another in the 1300s that was worse yet. The people had lived in the area and learned to survive with the climate changes for hundreds of years. The reasons for abandoning Mesa Verde and the Four Corners area were many, drought was only one. And it's a bit suspicious that a new, sun-based ideology arrives and starts to blossom, only to see all the people shortly move away and completely changed most of their ideas about community along the way. Rock art across the Southwest changed dramatically about the same time. One of the primary elements of their society that changed during the great migrations were the religious rituals and the imagery now identified as part of the Flower World Complex. Those were incorporated into their worldview and were thoroughly embraced by the Tewa people. Note: the Flower World Complex has nothing to do with the Katsina, Warrior or Sacred Clown societies, those societies formed later. The Flower World was about a paradise where people go after they die to live with their ancestors. It was interpreted as a flowery paradise filled with birds, butterflies and lush vegetation. Derivations of those images are still being replicated today in the northern Rio Grande Valley.

Some of the Hopi trace their ancestral routes back through the ancient Sinagua people of northern Arizona and the Ancestral Puebloans of the Four Corners area. Others trace their ancestry to the Little Colorado River area or to southeastern Utah or to Wenima in east-central Arizona (ancestral homeland of the Zuni people, too) or to Paquimé, and places in between. To honor those ancestors, some of the Hopi travel every year to various of the ancient sites and conduct religious services in remembrance of their ancestors.

Today's Hopi Reservation is surrounded on all sides by the Diné Nation, land set aside for a much larger tribe that entered and settled in the area just before the Spanish first arrived in force in the New World: the early 1500s. There has been animosity between the two tribes ever since. There has also been significant intermarriage. There was a time when the Diné would attack and kidnap Hopi women. From the Hopi perspective, any child born of a Hopi woman is a Hopi (descent is matrilineal). All forms of intermarriage have led to the development of new "houses" among the Diné.

The center of today's Hopi territory is located about 80 miles northeast of Flagstaff. There are twelve Hopi villages located in the areas of Hopi First, Second and Third Mesas. Those mesas rise up to 1,000 feet above the surrounding desert and afforded some degree of security from outside attack in the old days. Old Oraibi (on a high finger of Hopi Third Mesa) and Acoma Sky City both appear to have been inhabited for maybe a thousand years or more and both have somewhat equal claim to being the oldest still-inhabited settlements in the United States.

During Coronado's stopover at Zuni in 1540, he sent Pedro de Tovar and Frey Juan de Padilla with a group of soldiers to the Hopi area in search of Cibola, the legendary Seven Cities of Gold. They went to Awatovi, Sikyátki and Walpi and found nothing of interest to their gold-greedy eyes so they left. However, they did leave a bad taste behind.

There are two versions of the following story. The original (as related to Jesse Walter Fewkes in the 1890s) seems to have put Awatovi and the chief of Awatovi in the place of Walpi and the chief of Walpi (which is the usual version told these days). Back then, Awatovi was the larger and more populous village, but it was located well away from First Mesa on the southern side of Antelope Mesa. The majority of the people of Awatovi seem to have spoken Towa. Towa-speakers migrated into the area and built Awatovi, possibly after exiting the Fremont lands west of the Colorado River. Other Towa-speakers moved into the West Mesa Verde area for a couple hundred years before packing and relocating further east to the Jemez Mountains. Awatovi was destroyed by other Hopi villagers in the winter of 1700-1701. Some of the ritual specialists from Awatovi were saved from the destruction and spirited away to Walpi: the more clans a village had in residence, the more powerful the village. After that destruction, Walpi reigned as the preeminent Hopi village. Before that destruction, the Spanish were more focused on Awatovi than anywhere else in the area. After that destruction, the Spanish kept more distance.

So then, the original version of the story: When the Spanish first came near to the village of Awatovi, some of the people went out to meet them. At a short distance the Spaniards stopped. Pedro de Tovar got down off his horse and approached. The chief of Awatovi likewise moved forward. Neither could understand anything the other was saying so at arm's length, the chief of Awatovi extended his hand looking for an honorable, classic Nachwach clan handshake (the handshake of brotherhood and mutual respect). Pedro de Tovar looked at that and asked around among his men for a coin. Shortly, a coin was produced and de Tovar dropped it into the open palm of the Awatovi chief. The chief knew nothing of money and little about metal, but he knew a lot about personal honor and integrity: he knew not to trust a man who wouldn't even touch him, never mind shake his hand. It was an unforgetable insult and it showed a lot about the nature of the Spanish people of the time. Over the decades that followed, the Spanish only succeeded in expanding on that first impression.

Several Spanish explorers came and went over the next several decades but the first serious incursion by the Spanish came in 1629 when a group of Franciscan monks and soldiers arrived in the village of Awatovi. They immediately began trying to convert the residents of Awatovi to the Christianity-of-the-day. It was apparently failing until a perceived medical miracle by one of the padres changed things. The people didn't allow that particular padre to live much longer but the priests who came to replace him were even more of a problem. And they brought more soldiers.

From that first mission at Awatovi, the priests established a couple of satellite missions at Oraibi and Walpi. Those were attended by the priests off and on but they made no headway among the people there or anywhere else. They were also a bit nervous about the freshly destroyed ruins at Sikyátki (Sikyátki was destroyed, mostly by the people of Walpi, only a few years before the construction of the Franciscan mission at Awatovi). There were several other recently abandoned ruins in the area, too, but their stories were different.

When the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 happened, the Hopi acted simultaneously with their Rio Grande cousins and killed all the Spanish priests and soldiers they could find. And while they destroyed parts of San Bernardo de Aguatobi Mission, they didn't destroy it all. When the Spanish returned to northern New Mexico in 1692, it took them a couple years to solidify their hold on the Rio Grande pueblos. It was in 1696 that they sent someone to have a look at Hopi territory.

The Spanish were met immediately with hostility at every pueblo they went to. They also discovered that Walpi and most of the smaller pueblos around it had moved themselves up to a finger on the southern end of First Mesa, a much more defensible position. The only place the Spanish could even get in the door was Awatovi, and within a couple years that led to the complete destruction of Awatovi and the remains of San Bernardo de Aguatobi Mission. There were no more Christian establishments made in Tusayan until after the United States took possession.

To escape what was happening among the Rio Grande Pueblos in the 1690s, many Southern Tewa people who'd left the Santa Fe River Basin area in 1694 sought refuge among the Hopi. Their territory on the edge of the Rio Grande Valley had always been marginal but had become unlivable under the Spanish yoke. So they first went north to their Northern Tewa cousins and tried to settle in the Santa Cruz area. The Spanish didn't allow any non-essential travel at the time so they had to evade detection. They had to go around Santa Fe and get at least 20 miles to the north along the Rio Grande corridor. At the same time, there were active hostilities still happening between the Spanish and the Northern Tewa pueblos.

Population pressure and friction between them and their Northern Tewa cousins, plus problems with the local Spanish, resulted in the Southern Tewas killing a priest or two, then packing up and running west to avoid the coming retribution. Travel in those days was from watering hole to watering hole so some of them traveled quickly past Jemez to Laguna to Zuni to First Mesa. The rest took the same route but took more time: some of the women were pregnant and couldn't travel far until they'd given birth. In that way, they made and renewed connections among the people of the villages they passed by.

This is another area where two different stories are told. Some claim the people of Walpi sent representatives to the Rio Grande area to recruit Tewa warriors to come to First Mesa. Others claim the Tewas came begging for asylum at the doors of Walpi. Either way, the leaders of Walpi made a deal with the Southern Tewas in which the Tewas were allowed to stay as long as they kept guard over the access path to the top of First Mesa (in anticipation of coming Spanish retribution).

There is a story told about a Ute attack on Walpi being repulsed by Tewa warriors the very next year but the story isn't at all clear. In one version a traditional, seasonal Ute raid happens, just like any other regular Ute raid. Another version has the chief of the Walpis contacting the Utes and taunting them to attack and test the Walpis' new warrior friends.

However it started, the Utes did come raiding and they were beaten badly by the Tewas. A few Utes were allowed to live to carry the warning back to their people and the Ute problem stopped. The people of Walpi opted to let the Tewas stay. Part of the deal they struck gave the Tewas all the land east of a north/south line that ran across the mesa near Walpi. That included some good farmland down below the mesa. Today's Tewa Village and Polacca are built on some of that land south of the mesa.

On a northern finger of Second Mesa was a Southern Tiwa village named "Payupki," established by refugees from Alameda and Isleta who had fled to the area beginning in the early 1680s. After the destruction of Awatovi in the winter of 1700-1701, Payupki was targeted by a new cohort of Franciscan monks. The monks were being paid by the Spanish authorities in Santa Fe to try to get the "escapee" Tiwas to return and submit to Spanish rule. Eventually, relations with the Hopi on Second Mesa began to deteriorate and the Tiwas were convinced to abandon Payupki. In the company of several Franciscan priests, they headed back to the Middle Rio Grande area.

In 1741, 441 of them returned to the vicinity of Alameda Pueblo and surrendered to the Spanish authorities. A couple decades later they were finally allowed to build Sandia Pueblo near the destroyed Alameda Pueblo.

Back at First Mesa, there were abandoned structures at Hano, structures originally built by another group of Tewas I've traced back to the Chama River Valley near Abiquiu. Those people, the Asa people, abandoned Hano around 1600 CE because of drought and disease and went to the Diné settlements near Canyon de Chelly. They settled in there for about 50 years. They lost their history and their language in that time. Many intermarried with the Diné and established the High-standing House clan. After 50 years, some of them migrated back down to the Rio Grande pueblos. Others slowly went back to First Mesa and eventually settled mostly into Sichomovi (a new pueblo at the time, begun by migrants from Zuni but others came along later).

Hano is still populated and the residents still speak Tewa. The oldest Hopi village on First Mesa is Walpi, first established at the foot of the mesa near Coyote Spring around 900 CE. But the village was uprooted and moved to the top of the mesa and expanded in 1690 when the Hopi became fearful of reprisals from the Spanish after the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. All of the other populated villages near the foot of First Mesa were abandoned, too, and the people working together moved Walpi to the top of the mesa. This was a time when several more clans were added to the roster of Walpi as their separate pueblos were abandoned.

As much as the Hopi back then rejected all things Christian, they did embrace new Spanish agricultural products (apples, apricots, peaches and melons in particular) and new technologies (metal plows and hoes, new wood-working techniques and new textile weaving methods). They also embraced horses, cattle, sheep and burros, animals introduced by the Spanish that changed the way of life of tribes all across the West.

Prior to the Spanish arrival the Hopi had also domesticated turkeys. Turkey feathers are considered to be the most powerful feathers, even more powerful than eagle feathers. They are still used in the making of prayer sticks and kachinas. Turkey bones have been found in all archaeological digs in the area. Most of those bones were modified for use as tools for various purposes. Sometime after the Spanish arrival, the turkeys disappeared from the pueblos. By the 1800s there were only a few chickens running around and the people were herding sheep and cattle.

Hopi Pottery History

From Valdivia, Ecuador,

made between 3,400 and 1,500 BCE

I almost don't know where to start here. There was an early culture (the Las Vegas Culture, named for its proximity to today's Las Vegas River) along the Santa Elena Peninsula in Ecuador. The people were primarily hunter-gatherers but over the long term of their residency, sea levels rose, technology progressed, trade routes were formed and the people became more agrarian. They grew cotton and made textiles, they domesticated the bottle gourd and grew other grains, and they consumed a lot of seafood (the Pacific waters around the peninsula are extremely rich in fish and shellfish). Their culture began prior to 10,000 BCE and ended around 4,600 BCE. No one has yet figured out what happened to them or where they might have gone. Sea level rose about 100 feet during that time. The area is also prone to earthquakes and tsunamis. The Santa Elena Peninsula seems to have been depopulated and empty of people for the next thousand years. The culture of Valdivia rose in the same area around 3,500 BCE. Al Qoyawayma says that pottery unearthed in ancient ruins at Valdivia shows imagery that can be traced through the ages to the present (some modern Hopi potters make parrot effigy pots very similar to the ancient one in the photo).

Closer to the present, Hopi pottery has a history going back more than 1,000 years and many of the forms and designs in use today are direct descendants of those old pots. However, the actual making of Hopi pottery has been modified by a number of different elements over the years. After the Spanish introduced sheep, potters began using dry sheep dung to fire their pots. They used wood and coal before, and the soft coal available around the mesas required that firing happen immediately after the coal was removed from the mine, before it broke down into something else. It also required different ratios of clays, tempers and other elements to fire properly without cracking and without the decorations flaking off. The ancient pottery of Awatovi, Sikyátki and Kawaika'a were mostly fired using coal.

Sheep dung and cow patties changed all that, giving the potters freedom of location and timing. They also had to adapt the ratios of clay, tempers and other elements in their products to account for the lower temperatures attained with the firing materials. The potters also began to adopt some of the European ceramic designs. Shallow, flare-rimmed stew bowls and ring-based bowls began to appear. However, like all the other pueblos, the Hopi potters continued to use their hand-coil molding techniques and did not adopt the "potter's wheel."

From 1778-1780 and again several times through the 1800s, drought and outbreaks of European diseases forced significant numbers of Hopis to move temporarily to Zuni, Zia and Acoma Pueblos. It was a time when the Hopi pottery tradition seems to have been dying out at First and Second Mesas. Under the Spanish principle of "village specialization," the making of Hopi pottery was kept alive only at Oraibi. The one area where that did not apply was the area settled by the Tewa around First Mesa. The Hopi-Tewa produced pottery consistently through the years and never let it go.

An outbreak of smallpox at Oraibi in 1882 caused many people to move to Zuni. The cross-pollination that happened caused their formerly unslipped tan, orange and light yellow creations to add a white, yellow, pink or pale brown slip. Pots from that time resemble Acoma and Zuni pots of the period. New pottery shapes and designs also emerged during those times.

On their return to Hopi a few years later, they had a problem with the local white clay they had available for slip: while being fired, it shrank differently than the clay body it covered. That produced a crackled surface that wasn't very popular with the tourists. This was the time of transition from "Polacca A-C" (common from 1780-1880) to "Polacca D" ware, buff-colored clay with a thin white slip. Polacca C ware is what Nampeyo (1858-1942) is said to have been producing at the beginning of her days as a potter. Polacca D is also the point where Sikyátki symbols and imagery began to appear again: Polacca D was made primarily for the traders and tourists.

Then the railroad traders arrived and started ordering large volumes of pottery to sell to their travelers. It was almost the death of traditional Hopi pottery. Then the archaeologists arrived and "discovered" Jeddito yellow ware. Nampeyo had already refined her process further and moved to painting directly on a polished yellow clay body. That's where the Sikyátki Revival (Hano Polychrome) really began (1885-1910).

Nampeyo lived in the Tewa village of Hano at the base of First Mesa. Her imagination was fired by the ancient potsherds she found while walking around near the ruins of Sikyátki, a village inhabited between 1375 and 1625. The ruins were only a couple miles from her home in Hano. The Sikyátki style required the use of a fine-textured yellow clay rather than the heavier yellowish-white slip the Hopi had adapted after their return from Zuni. That finer clay allowed Nampeyo to develop an unslipped yellow body with a high polish as a canvas for her painted designs. She decorated her pottery with stylized images of butterflies, birds, moths and other designs, ushering in a whole new era of Hopi pottery making. The dynasty of pottery artists that began with her is still dominant among Hopi potters.

The full story has some amazing twists and turns in it. The Book of Hopi talks about the migrations that went on for thousands of years with tribes and clans criss-crossing the countryside in their search for the "Middle Place." Archaeologists and geneticists have been able to trace the genetic roots of the migrations going back to the days of the Bering Land Bridge, between 15,000 and 20,000 years ago. Al Qoyawayma talks about finding designs from today's Hopi vocabulary on ceramics unearthed in Valdivia, Ecuador, and dated to the time of Moses or before. When we look at the archaeology and the oral histories of many tribes and clans, we see lots and lots of migration happening over thousands of years, and not just in the area spanned by the southwestern United States.

When it comes to the area of Kayenta-Tusayan itself, we can see how different groups came together and then split apart again, and again, and again. We see settlements comprised of people from all over the region, coming together in a boiling pot of clans, languages and ritual practices at different times and for different reasons. Al Qoyawayma also says the ancient village of Sikyátki was a settlement of his Coyote Clan, with origins, religion, language and traditions different from the Hopi we know today. At the same time, archaeologists say Sikyátki was a settlement of the Kokop (Firewood) Clan, a group that likely spoke an ancestral version of Towa. There's new evidence that Towa was brought into the region by migrants from the Fremont culture area west and north of the Colorado River.

The Kokop Group, as outlined by the elders of Walpi and Sichomovi to J. Walter Fewkes in 1895, consisted of the Firewood, Coyote, Wolf, Yellow Fox, Gray Fox, Pinon, Juniper, Bow, Masau'u (Death God), Eototo and two unknown bird clans.

Awatovi, nearby on the southwestern side of Antelope Mesa, was begun a few decades before Sikyátki and it survived Sikyátki by about 75 years. Then it, too, was destroyed by the people of Walpi in the winter of 1700-1701. Oral histories say that Sikyátki was completely wiped out, men, women and children. In reality, some of the clan ritual specialists were allowed to survive. Their clans were just transplanted to other villages and their dances integrated into the local annual schedule. Not all members of the same clan nor did individual members of any one clan relocate to any one village. The fracturing and resettlement of clans and ritual specialists has led, over time, to some clans dying out at some villages. When those villages dance now, there are empty spaces in their dances. There are so many empty spaces in some dances that the dances can't be danced and the functions of those dances are lost.

When it comes to Awatovi, there is also evidence that some of the ritual specialists were allowed to survive the massacre there and carry their knowledge, rituals and dances to other nearby settlements. There is also evidence that some of the women and children were spared, only to be killed a short distance away shortly thereafter. The people of Awatovi spoke several languages but the primary ones seem to have been Towa and Keres. The nearby pueblo of Kawaika'a seems to have spoken primarily Keres.

However we want to look at it, today's Hopi are descended from families, groups and clans that came from as far north as central Utah, as far south as Paquimé in Mexico, as far east as the Rio Grande and as far west as the Grand Canyon (the Hopi knew of the Paiute and considered them to be witches and demons to be killed on sight). And as each of the groups and clans came together, the Hopi language evolved. It's a union of families at different stages of culture, each having their own religious traditions, secular customs and separate languages. Even today, there are slight differences in the Hopi language as spoken by residents of each different village, the most different being the dialect spoken at Old Oraibi.

On the other hand, Hano, in its different incarnations, seems to have always spoken Tewa. Tewa and Hopi are unrelated to each other. The agreement reached around 1698 between the Hopis and the Southern Tewas was that the Tewas could speak Hopi but the Hopis would never speak Tewa. Tewa as spoken in the vicinity of First Mesa is now identified as "Arizona Tewa" and is classed as a "threatened" native language. There has been contact and intermarriage between Hano and the Rio Grande pueblos but the Tewa spoken at each end of that connection has slowly diverged since 1700.

A view from the edge of Old Oraibi

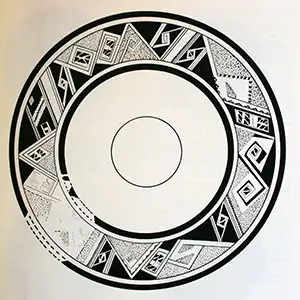

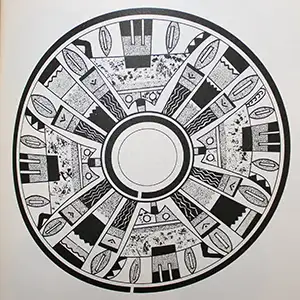

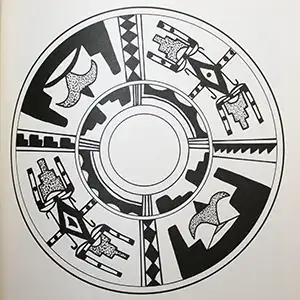

Sikyatki bowl photos courtesy of Jay Cross, CCA 2.0 License

Design pattern images are from Historic Hopi Ceramics

Hopi Potters

- Hopi

- Karen Abeita

- Alice Adams

- Sadie Adams

- Loren Ami

- Ramona Ami

- Reva Polacca Ami

- Flying Ant

- Andrea Auguh

- Nathan Begaye

- Hattie Carl

- Bonnie Chapella

- Grace Chapella

- Karen Charley

- Lena Charlie

- Lowell Chereposy

- Debbie Clashin

- Kathleen Collateta

- William David

- Verla Dewakuku

- Preston Duwyenie

- Feather Woman

- Larson Goldtooth

- Vina Harvey

- Antoinette Honie

- Patricia Honie

- Daisy Hooee

- Rondina Huma

- Stella Huma

- Violet Huma

- Gloria Kahe

- Valerie Kahe

- Alton Komalestewa

- Jacob Koopee

- Claudina Lomakema

- Lorna Lomakema

- Steve Lucas

- Gloria Mahle

- Garrett Maho

- Patty Maho

- Amber Naha

- Burel Naha

- Helen Naha

- Nona Naha

- Paqua Naha

- Rainy Naha

- Sylvia Naha

- Tyra Naha

- Randall Sahmie Nahto

- Les Namingha

- Lillian Namingha

- Priscilla Namingha

- Bessie Namoki

- Lawrence Namoki

- Nampeyo of Hano

- Adelle Nampeyo

- Carla Claw Nampeyo

- Daisy Nampeyo

- Darlene Nampeyo

- Dextra Quotskuyva Nampeyo

- Donella Nampeyo

- Elva Nampeyo

- Fannie Nampeyo

- Gary Polacca Nampeyo

- Hisi Quotskuyva Nampeyo

- Iris Nampeyo

- James Nampeyo

- Leah Nampeyo

- Loren Hamilton Nampeyo

- Melda Nampeyo

- Miriam Nampeyo

- Nellie Nampeyo

- Neva Nampeyo

- Rachel Namingha Nampeyo

- Rayvin Nampeyo

- Tonita Nampeyo

- Charles Navasie

- Dawn Navasie

- Dolly Navasie

- Eunice Navasie

- Fawn Navasie

- Grace Navasie

- Joy Navasie

- Loretta Navasie

- Marianne Navasie

- Maynard Navasie

- Garnet Pavatea

- Clinton Polacca

- Thomas Polacca

- Vernida Polacca

- Laura Preston

- Alice Puhuhefvaya

- Al Qoyawayma

- Hisi Nampeyo Quotskuyva

- Marcia Rickey

- Jean Sahme

- Nyla Sahmie

- Rachel Sahmie

- Beth Sakeva

- Cynthia Sequi

- Dee Setalla

- Pauline Setalla

- Bobby Silas

- White Swann

- Dianna Tahbo

- Mark Tahbo

- Ted H. Tahbo

- Eli Taylor

- Marjorie Tewaguna

- Tyra Tewawina

- Unknown Hopi Potters

- Myrtle Young

- Ethel Youvella

- Nolan Youvella

- Susie Youvella

- Wallace Youvella