Nampeyo of Hano

Hopi

Iris Nampeyo was born around 1860 in Tewa Village at the base of First Mesa. Her mother was White Corn of the Hopi-Tewa Corn Clan, her father Quootsva, a member of the Hopi Snake Clan from nearby Walpi. The name "Iris" most likely was given to her by someone working at the nearby Indian Health Services outpost. It was at Indian Health Services that Iris was diagnosed with trachoma, then an untreatable infection in the eyes that would eventually blind her.

Four generations of Nampeyo's family in 1901: Annie on the left holding Rachel, White Corn in the middle, Nampeyo on the right

According to tradition, Iris was born into her mother's clan (the Corn Clan) and grew up under her mother's wing, although she learned the basics of traditional pottery making from her father's mother. In the late 1870s she was making money selling some of her creations to the trading post operated by Thomas Keam over in Keam's Canyon. Around 1881 she was already a noted producer of Walpi Polychrome pottery when she married Lesou, her second husband. As time went on, she became increasingly interested in older and older Hopi pottery styles and designs. Her home was only a few miles from the ancient pueblo of Sikyátki and she found abundant inspiration among the potsherds she found scattered throughout those ruins.

She was good enough at her trade to be able to discern the multiple shapes and designs employed by those ancestral potters. It took her a while to find the clay source they had used, then more time to work the clay and learn to polish it to where decoration could be added to the bare clay body rather than over a thin slip. At one point, a collapse on the side of the mesa buried the source of Sikyátki white clay and the use of white slip was suspended until a new source was found near Coyote Springs on Second Mesa (Nampeyo's family owned a sheep ranch over there). That said, Nampeyo stopped using any white slip around 1910 and focused primarily on using the bare Jeddito yellow clay body for her canvas.

Eventually she got it right and her development of those styles and designs led to the Sikyátki Revival period and that has led to a revival of the whole world of Hopi pottery. Nampeyo also prowled the sites of other ancient Hopi villages and found potsherds from other times and incorporated those, too, into her styles and designs. When the archaeologists came to First Mesa looking for potters to recreate the prehistoric pottery they'd found at Sikyátki, Nampeyo had already been producing pieces like it for several years. She was particularly skillful in making her products and painting their designs. They were a commercial success, both in the US and abroad. She also used other ancient Tewa techniques in the firing of her pots and in the processing of fired pots after firing.

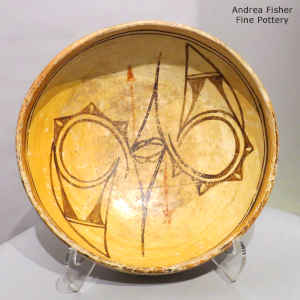

Nampeyo's first pots were made most likely in the days of transition between the Polacca Polychrome styles that had been produced in the Hopi mesas since about 1780 to what became known as "Polacca D," denoting the use of white slips over buff clay bodies and red and black decorations. Many of the designs came from potsherds a thousand years old, like the stylized avian-like creatures (usually identified now as "bird elements"). Other designs she took from the rock art that had decorated the canyon walls of the Hopi mesas for thousands of years.

In the early 1890s, Jesse Walter Fewkes arrived and began his archaeological dig at the prehistoric village of Sikyátki. His workers found many old pots buried there, some whole, most broken but easy enough to reconstruct because all their pieces were together in one spot. As his expedition was financed by Mary Hemenway, one of the benefactors of Harvard College, the vast majority of his findings were transported there and can now be found buried in the back rooms and basements of the Peabody Museum. However, Fewkes also knew that Nampeyo's work was excellent for the time and was worried that her creations could become confused with those of the ancient potters. So he concocted a story that made it seem as though she had learned her methods, shapes and designs from his efforts... That story associated his name with hers and in some respects, his fame became tied to hers... But the physical evidence points to her producing Sikyátki-style pottery with Sikyátki designs several years before Fewkes arrived in the area. Fewkes did an excellent job of cataloging and noting everything he came across in Hopi society, although for many of his ancient stories he relied on a single source too often. As for the story about Fewkes introducing Nampeyo to the Sikyátki shapes and designs, that's just another case of an Anglo "expert" taking advantage of a Native American to puff up his own reputation.

Fewkes may have also been why she became known as "Nampeyo of Hano." Hano was the name of a village that was built and abandoned before Nampeyo's Tewa ancestors migrated to Tusayan (the Spanish term for the region of the Hopi mesas). The Southern Tewas arrived in the late 1690s. After proving themselves as warriors, the people of Walpi allowed them to settle in the remains of the abandoned Hano. The Tewas settled in and spread out, that's how the name "Tewa Village" came into use. However, the Hopis who acted as interpreters for Fewkes insisted on using the name "Hano" for the entire area. Tewa Village was built very close to the remains of ancient Hano and it seems the abandoned Hano pueblo had been built by prehistoric Tewa migrants and abandoned around 1600, well before the Southern Tewas arrived and Tewa Village came to be. When looking at the records of who among the Hopi were actually employed or interviewed by Fewkes, most were not from First Mesa and were not necessarily privy to First Mesa oral history: each pueblo (and clan) had their own versions of the old stories.

Nampeyo's sight began to fail around 1900 and by 1920 she was making her pottery completely by feel. Her husband, daughters and other family members polished, painted and fired them for her. When her granddaughter Daisy came back to Hopi after graduating from L'Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and taking a round-the-world trip with her Anglo benefactor (Anita Baldwin of Santa Anita Race Track fame), she painted for her grandmother, too.

Nampeyo's children: Annie (b. 1884), William Lesou (b. 1893), Nellie (b. 1896), Wesley (b. 1899), and Fannie (b. 1900). In Nampeyo's final years, Fannie was her primary painter. Around 1920 Fannie began signing the pottery she made with her mother as: "Nampeyo Fannie." Pottery she made by herself she signed "Fannie Nampeyo."

There are a few pots around with "Daisy Nampeyo" signed on the bottom. With those it's hard to determine who made the piece itself as Nampeyo and Daisy were both master potters (as was Fannie). Daisy's knowledge of design vocabulary was similar to Nampeyo's but Daisy used different elements in her designs to create tension. That said, Nampeyo had essentially 6 design strategies and Daisy employed most of them. Fannie, on the other hand, only employed a couple: the vast majority of Fannie's work is decorated with variations of the migration pattern.

In 1922, Nampeyo was commissioned by the owner of the Quapaw Bath House at Hot Springs, AR, to create 4 effigies similar to Tesuque munas, aka "Rain Gods." The figures were delivered in April 1922 and they varied between 8 3/8 inches and 9 5/8 inches in height. The size of them and the quality of the work showed they were not meant for the tourist trade. When the Quapaw Baths opened to the public later that year, the effigies were on display in the halls and drew a lot of attention. A few years later, the effigies were donated to either the Department of the Interior or the National Park Service, where they disappeared and haven't been seen since. They seem to have been the only effigies ever attributed to Nampeyo.

When she died in 1942, Nampeyo was quite probably the most photographed woman in the Pueblo pottery world. She also left behind a large family of Hopi-Tewa potters that only seems to grow and improve with each generation.

Note: "Nampeyo" is a title, not a family name. The title is generally reserved to the woman who is head of the Hopi-Tewa Corn clan at First Mesa. It is passed mother-to-daughter-or-other-female-relative. The office is never held by a man. Technically, no man should ever use it as part of their name/signature. The office and title passed from White Corn to Iris to Fannie to Tonita to Melda... As of 2021 the office was held by Rachel Sahmie Nampeyo, but Rachel passed on in late 2022.

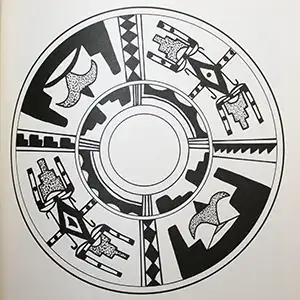

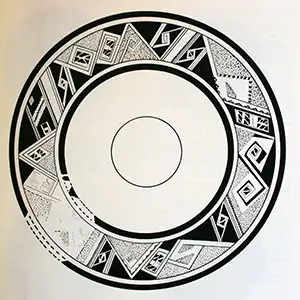

Images of Design patterns from Historic Hopi Ceramics

Hopi Potters

- Hopi

- Karen Abeita

- Alice Adams

- Sadie Adams

- Loren Ami

- Ramona Ami

- Reva Polacca Ami

- Flying Ant

- Andrea Auguh

- Nathan Begaye

- Hattie Carl

- Bonnie Chapella

- Grace Chapella

- Karen Charley

- Lena Charlie

- Lowell Chereposy

- Debbie Clashin

- Kathleen Collateta

- William David

- Verla Dewakuku

- Preston Duwyenie

- Feather Woman

- Larson Goldtooth

- Vina Harvey

- Antoinette Honie

- Patricia Honie

- Daisy Hooee

- Rondina Huma

- Stella Huma

- Violet Huma

- Gloria Kahe

- Valerie Kahe

- Alton Komalestewa

- Jacob Koopee

- Claudina Lomakema

- Lorna Lomakema

- Steve Lucas

- Gloria Mahle

- Garrett Maho

- Patty Maho

- Amber Naha

- Burel Naha

- Helen Naha

- Nona Naha

- Paqua Naha

- Rainy Naha

- Sylvia Naha

- Tyra Naha

- Randall Sahmie Nahto

- Les Namingha

- Lillian Namingha

- Priscilla Namingha

- Bessie Namoki

- Lawrence Namoki

- Nampeyo of Hano

- Adelle Nampeyo

- Carla Claw Nampeyo

- Daisy Nampeyo

- Darlene Nampeyo

- Dextra Quotskuyva Nampeyo

- Donella Nampeyo

- Elva Nampeyo

- Fannie Nampeyo

- Gary Polacca Nampeyo

- Hisi Quotskuyva Nampeyo

- Iris Nampeyo

- James Nampeyo

- Leah Nampeyo

- Loren Hamilton Nampeyo

- Melda Nampeyo

- Miriam Nampeyo

- Nellie Nampeyo

- Neva Nampeyo

- Rachel Namingha Nampeyo

- Rayvin Nampeyo

- Tonita Nampeyo

- Charles Navasie

- Dawn Navasie

- Dolly Navasie

- Eunice Navasie

- Fawn Navasie

- Grace Navasie

- Joy Navasie

- Loretta Navasie

- Marianne Navasie

- Maynard Navasie

- Garnet Pavatea

- Clinton Polacca

- Thomas Polacca

- Vernida Polacca

- Laura Preston

- Alice Puhuhefvaya

- Al Qoyawayma

- Hisi Nampeyo Quotskuyva

- Marcia Rickey

- Jean Sahme

- Nyla Sahmie

- Rachel Sahmie

- Beth Sakeva

- Cynthia Sequi

- Dee Setalla

- Pauline Setalla

- Bobby Silas

- White Swann

- Dianna Tahbo

- Mark Tahbo

- Ted H. Tahbo

- Eli Taylor

- Marjorie Tewaguna

- Tyra Tewawina

- Unknown Hopi Potters

- Myrtle Young

- Ethel Youvella

- Nolan Youvella

- Susie Youvella

- Wallace Youvella