Shapes and Forms: Jars, Pots and Ollas

Polychrome olla decorated with bird element, fine line, rain and geometric designs, by Robert Patricio, Acoma

9 1/2 in H by 12 1/4 in Dia

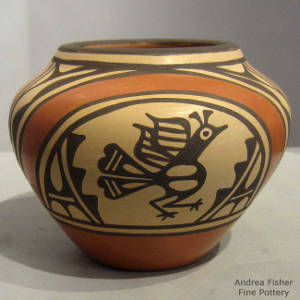

Polychrome jar decorated with roadrunner, cloud and geometric design, by Ruby Panana, Zia

5 3/4 in H by 6 in Dia

Large polychrome jar decorated with bird, floral and geometric design by Thomas Tenorio, Santo Domingo

13 1/4 in H by 10 1/2 in Dia

"Jars, Pots and Ollas" covers a wide range of Native American pottery. Olla is a Spanish term for "large pot." It implies a large storage jar or water jar. In excavating many ancient ruins, archaeologists (and illegal pot hunters) have found many large storage jars.

There was a time, too, when the Southern Tewa potters of the Galisteo Basin area and the Eastern Keres potters of the middle Rio Grande were coating their pottery with leaded pigments to seal them better. That area is close to the ancient turquoise and lead mines in the Cerrillos Hills. That pottery was so popular back then that pieces of it have been found scattered from the Colorado River east across the Llano Estacado (the Staked Plains) of west Texas and into the forests west of the Mississippi. The Spaniards ended that production in 1696 when they seized those mines for the lead to make bullets and cannon shot. They forbade the puebloans access. Spanish-introduced diseases were again taking a toll on the whole area and the few remaining Southern Tewas finally abandoned their impoverished pueblos and moved north in an attempt to merge with their northern Tewa brethren. Their reception there wasn't so friendly and they ended up relocating to the Hopi First Mesa area. Others moved downstream along Galisteo Creek to Santo Domingo.

There was also some lead-based glazing happening in the Zuni area around the same time but it stopped before the Spanish found the source of their lead ore and they never suffered that disruption.

At Tuzigoot National Monument near Clarkdale, AZ, I came across several large ollas on display in the Visitor Center. Sadly, none of the staff knew any more about them than what was printed on the signage. So I went home and did some research.

Whgen they had been found, those now reassembled ollas had another large jar inside them. The two jars were buried in the floor of a living space in the basement floor of the pueblo. The outer jar was filled with water, they stored perishables in the inner jar and the whole thing acted as a "refrigerator." The dirt provided insulation against the heat while evaporation kept the interior jar cool.

Tuzigoot was a Sinagua pueblo in the Verde River Valley, part of the Verde River Confederation. Construction there began when Sinagua from the area around the Sunset Crater eruption arrived in the area in the latter part of the 1000's CE. Tuzigoot has been dated to have been founded around 1100 CE and occupation continued until about 1400 CE when the whole area was abandoned. It seems the early 1380's were significantly cooler and overly wet with lots of flash flooding. After about 1390 the area got really hot and dry (the entire Southwest suffered a nasty drought through the late 1390s and early 1400s). It was about the same time as that abandonment that the more warlike Tonto Apaches and the Yavapais moved in. How closely timed those migrations were may be why most pueblos in the area were burned as they were being abandoned.

As a product of essentially sedentary farmers, jars and ollas were also used for corn and grain storage: they kept the bugs, snakes and rodents out. In many ancient pueblos they were also used for cooking food. Many of today's puebloans still prefer to have their beans cooked in a hand-made lidded micaceous pot.

There was also a need for the "seed pot": a hard ceramic vessel for storing seeds in. They all had a hole that could be plugged by a stick or similar device and would protect the seeds inside from predators like rodents, lizards, snakes and birds. When it came time to plant the seeds, the pot would be broken open and the seeds released. That made the annual renewal of the seed pot supply an imperative. As seed pots also carried the hopes and prayers of the pueblo inside them, the pots were made in a state of constant prayer and their surfaces were decorated with the designs of prayer.

In the early days of Spanish colonialism, the European settlers traded with the various pueblos for their storage jars and cookware. That market exerted a strong influence on the shapes produced by pueblo potters.

When Amish traders arrived in the mid-1800's with enameled cooking ware, the production of utilitarian pottery almost completely died out. When the tourist market opened up in the 1880's and that demand for pottery increased, it wasn't the same in most pueblos. The only pueblo where large hand-made utilitarian clay jars were still being made was Zia. And by then, the shapes of and designs on the pottery of most pueblos had already been somewhat polluted by the influence of the Spanish. Other Euro-Americans flooded into the area after the Mexican-American War of 1847-1850.

As an example: Acoma potters long used Mimbres-influenced images of birds in their decorations. When the Amish arrived, they brought wooden crates filled with enameled cookware. On the exterior of those crates was the Amish parrot. That Amish parrot has become the "traditional" parrot painted by most Acoma potters. Machine-woven cloth came with imprints of all kinds of squiggly geometric designs, native to older European forms. Many of those squiggly shapes have made their way into various pueblo pottery vocabularies because of the potters' efforts to cater to the Anglo market. Some traditional pueblo designs have been modified to more closely resemble those European designs.

Maria Martinez and her husband Julian made half-a-dozen large black-on-black jars around 1936-38. The diameters were all between 24 inches and 28 inches. They seem to have been made purely for the art involved, although the prices their work commanded back then might been the incentive to go that large. They never made anything else that large before or after: the timing especially didn't work out. I found one at the School for Advanced Research (in Santa Fe), another at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (also in Santa Fe) and a third at the Toledo Museum of Fine Art (in Toledo, Ohio). The one in Toledo is in mint condition. The only potters I've come across who've made any jars that size since have been from Mata Ortiz.

Some Hopi, Zuni, Zia and Acoma potters still produce large ollas but mostly as artwork for sale to the descendants of the Euro-American invaders. A large jar these days may be 12 inches in height and diameter. Most are smaller, between 4 inches and 10 inches in height and diameter. I'm seeing most market action in the area of pots small enough to be packed easily and placed in the overhead storage bins of most commercial aircraft. Considering that so many of the people younger than baby-boomers are becoming globe-trotting nomads, that particular size of pottery may be the short-term future for most Puebloan and Mata Ortiz potters.

Plain brown jar decorated with a rope biyo', fire clouds and pine pitch coating, by Alice Cling, Navajo

5 1/4 in H by 3 1/2 in Dia

Polychrome jar decorated with a deer, heart line and geometric design, by Anderson Peynetsa, Zuni

5 in H by 7 1/4 in Dia

Sikyatki-style jar with eagle tail and geometric design, by Rachel Sahmie Nampeyo, Hopi

8 1/4 in H by 8 3/4 in Dia