The Salado Culture

There doesn't seem to have been a distinct Salado culture as much as there was a Salado ideology. The name was originally applied to a form of red ceramic decorated with red, black and white paints: Salado Polychrome. There is speculation the makers of Salado Polychrome used the Tonto Basin as a sort of headquarters from where they sent artisans, ritual specialists and traders into other nearby societies to establish relations and eventually convert them to the new religion. Salado Polychrome pottery has been found as far south as Paquimé in northern Mexico. Excavations in Salado ruins have found feathers from macaws (from southern Mexico), copper bells (from the west coast of Mexico) and seashells (from the Sea of Cortez), testimony to long trade routes that were shared with pieces of turquoise headed south from Salado territories.

Archaeologists working in the area have found evidence of Late Archaic indigenous people with a more Mogollon influence, in the valley before the Hohokam first arrived in the 600s. When the Hohokam arrived, they built separately and maintained their separate society and religion but engaged in trade with the locals. Over time, all business became funneled toward the Hohokam Core (Valley of the Sun). Then, around 1050 CE, the Hohokam regional structure retracted and reorganized. At that time, virtually all the Hohokam in the Tonto Basin returned to their desert cities and didn't return.

The indigenous people who had been in the basin first, were still there. And they went back to their old ways: trading with people to the north and northeast among the Mogollon and Ancestral Puebloans.

There was a large influx of people from the Kayenta area into the Tonto Basin around 1250 CE. The newcomers built many constructions in the Tonto Basin but a significant number of them have since been drowned beneath Roosevelt Lake. Some of the better preserved ruins are included in Tonto National Monument but there are others throughout the valley and in the nearby mountains. The Salado people also maintained their separate society and religion, as the Hohokam had done before them. As the decades passed, the layouts and designs of the pueblos they built changed, becoming more defensive in location and construction. The Tonto Basin was being depopulated by about 1350 as they were starting to build their homes in alcoves high on the cliffs in the Sierra Ancha Mountains. By 1450 they had essentially disappeared.

The Tonto Basin diet consisted of beans, pumpkins, maize, squash, amaranth, whatever berries were in season and whatever their hunters could bring in. They built irrigation systems and grew cotton to supply a primitive textile industry. After the Hohokam left, the indigenous people also used cotton to trade for ceramic wares.

The Salado culture was in place for long enough to evolve intricate woven patterns in shirts and such. Sadly, unprotected cotton doesn't survive long in the Southwest climate. Textiles are a whole section of prehistory that we see extremely little of. It has been speculated that textiles carried more of the spiritual story of the Southwest than pottery, pottery has just been able to carry that story for longer. Textiles, though, were more easily transported cross-country and, used in masked rituals, spread the stories far wider. Sadly, there are very few left who can interpret the stories on the old pottery and tell the fullness of them: the depth of meaning has been lost to time.

A Salado pueblo in the Sierra Ancha Mountains

The Tonto Basin is watered by the Salt River (hence the "Salado" name) and the earliest settlements were built in the open valley. As time passed and the population increased, the people spread out and built higher and higher, away from the river and into the surrounding mountains. Some of the newcomers were from the Kayenta-Tusayan area to the north, others were from the Mogollon settlements to the east. They made it a time of significant innovation in the making of local pottery. The most distinctive change in pottery decorations was the addition of a white outline around the major design elements. Some migrants from the Salado area continued moving south into the Safford and Aravaipa Valleys and eventually reaching Paquimé before returning north to the Tonto Basin. They made pottery at virtually every stop in their journey, leaving trails of Salado Polychrome sherds behind.

Everywhere they went, the Salado people kept to themselves and practiced their own religion in their own enclaves. They adapted their pottery-making ways to fit local clays and tempers but they always produced the same red pottery with white and black geometric designs. They also built a large network of prosperous obsidian traders across the Southwest and into northern Mexico.

Then came the Apaches, looking for good land to take from someone. Their efforts pushed the Salado people further into the mountains, up the water flows to their sources until eventually, by the late 1400s, they had abandoned the area. Some of the people went north toward the Hopi mesas, some went east over the hills to Zuni and Acoma, some went south and west, to the then-deserted Hohokam homeland.

At the end of the 1400s there was another drought, one that was significantly worse than the "Great Drought" of the late 1200s. The Zuni people had been expanding their territory to the east but the weather in the last part of the 1400s forced them to retreat back to their central homeland along the Zuni River. The Salado people didn't have a lot of choices: the gods they had chosen to worship apparently weren't the correct gods for the time either. It's quite possible their religious world view collapsed under the volcanic ash-laden skies of the mid-1400s, same as their religious world view had previously arisen under likewise volcanic ash-filled skies in the mid-1200s.

That Kayenta migration also acted like a diaspora: they stayed in contact with each other over the years, continuing to do business together and continuing to practice their religious customs in private. The designs and shapes of their pottery remained true to a single vision. They generally built enclaves of their own, close to but never merging into any other local groups of people. They also controlled a large amount of the obsidian trade across the Southwest and northern Mexico. The pottery and the obsidian trade was enough to make them relatively wealthy for the time. They also dealt in turquoise. Turquoise was even more valuable, to people further and further away.

The Griffin Wash ruin, a Salado culture site in the Tonto Basin

What the Salado left behind were many masonry constructions, and sandals and baskets woven of yucca and agave (any woven cottons didn't survive the passage through time). They left bone tools and Salado Polychrome pottery, both decorative and functional. They also left macaw feathers (from central Mexico), copper bells (from northern Mexico) and seashells (from the Sea of Cortez), testaments to the trade they enjoyed with far-off cultures.

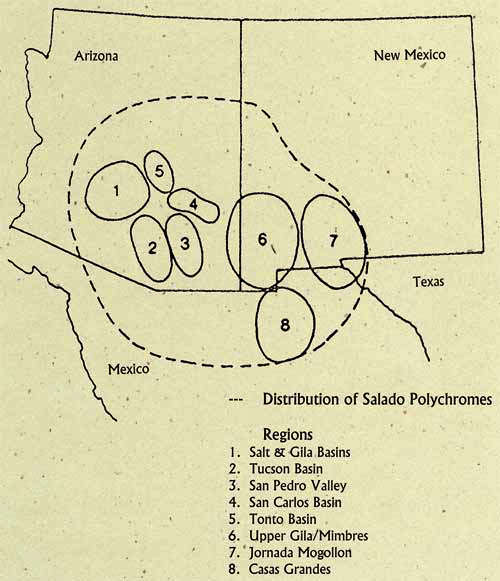

The Salado figure prominently in this story because of their Salado Polychrome pottery. While many ancient Salado Polychrome potsherds have been found in the Tonto Basin, close versions have also been found spread from northern Arizona to northern Mexico and from the Salt River basin in central Arizona to the Tularosa basin in central New Mexico.

The Salado style came into its own around 1280 CE and remained in use across the southwest until about 1450 CE. By then, global severe weather changes and the arrival of various flavors of aggressive Athabascans in the neighborhood were changing everything.

Routes of the Kayenta-Tusayan

migration between 1100 and

the early 1200s CE

Archaeologists feel the design styles had evolved earlier in northeastern Arizona (Kayenta) and migrated southward from there with a migration out of the Kayenta pueblos in the early 1100s. Their design styles and techniques for making pottery have been traced as far south as the San Pedro Valley in southern Arizona.

Around 1250 another series of waves of immigrants arrived from the Kayenta-Tusayan area. Again, they brought new technology for the making of pottery. Versions of their pottery have been traced into northern Mexico to Paquimé and further south.

The 1400s CE was a time of major turmoil in the southwest as there were a couple major, years-long droughts and people everywhere were on the move. The weather forced them to leave broad swathes of almost empty countryside behind. Then the Apaches moved in and got themselves settled before the first Spaniards came through.

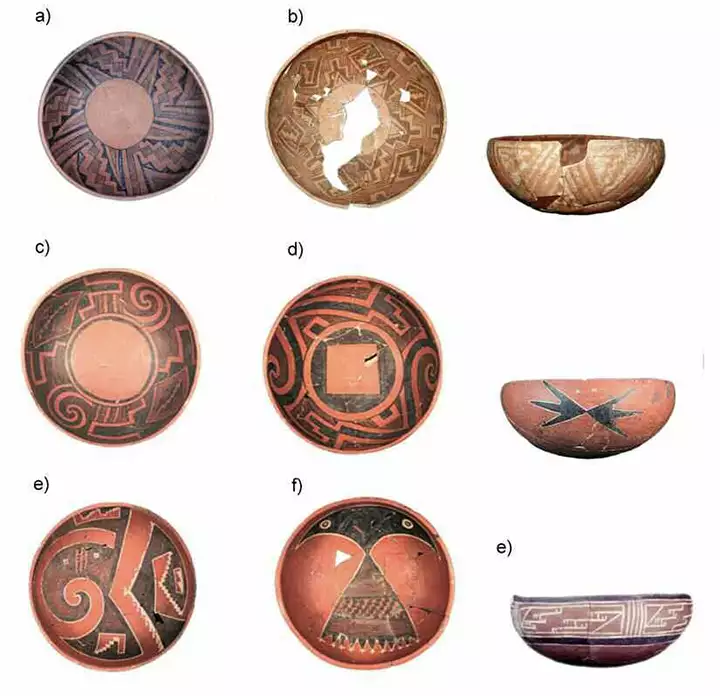

All types of Salado Polychrome share a number of broad categorical similarities. However, there was significant variation over the roughly 170 year time span of its production. The base paste was generally brown to reddish-brown in color and was tempered with sand. Usually a red and/or white slip were used to cover both the interior and exterior of the vessel. Black paint was used on one or both surfaces, usually surrounded by a white slip. The black paint used was most commonly organic but a mix of organic and mineral paints appears on some vessels.

Studies have shown that Salado Polychrome was produced across the full range of territory in which it has been found. It didn't emanate from a single production area and spread through trade. It more likely spread as knowledge, as individual potters migrated cross-country and produced new vessels using new clays and pigments that were available wherever they settled.

A collection of White Mountain/Salado redware bowls

Most were found at Grasshopper Pueblo

Map showing the distribution of found Salado Polychrome pottery

One of the Salado pueblos at Tonto National Monument

Other small photos courtesy of the National Park Service

Griffin Wash photo courtesy of the Center for Desert Archaeology

White Mountain bowl images are courtesy of Van Keuren, except "B", which is by Matt Peeples and Garrett Trask