Design Elements: The Clay Body

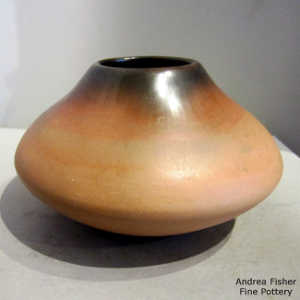

Brown jar decorated with a black rim and fire clouds

by Jody Folwell, Santa Clara

4.5 in H by 7.5 in Dia

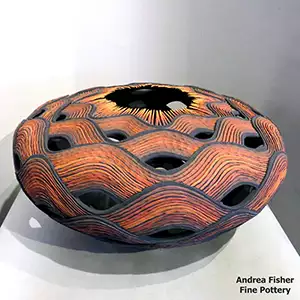

Polychrome sea urchin-like jar with a tiny coil design and cutouts

by Richard Zane Smith, Wyandot

13.5 in Dia by 6.75 in H

Polychrome bowl decorated with a Sikyátki-Revival stylized insect, sky band, kiva step and geometric design

by Nampeyo of Hano, Hopi

2.5 in H by 8.25 in Dia

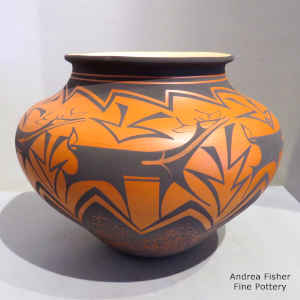

Polychrome jar decorated with a deer, heart line and geometric design

Polychrome jar decorated with a deer, heart line and geometric designby Anderson Peynetsa, Zuni

6.5 in H by 8.5 in Dia

Clay is basically powdered earth. Specifically, it is sedimentary rock made up of silicate minerals with sheet-shaped chemical structures that provide plasticity in the right conditions. Deposits of clay are formed through prolonged erosion of larger pieces of material. Ancient native potters used locally abundant clays to shape basic pottery forms. The clay was "mined," pulverized by grinding, cleaned of organic and other foreign materials, and then mixed with water to a workable consistency. Then the clay was formed into a pot by using one of two basic methods: hand-coiling or paddle-and-anvil.

In the hand-coil method, wet clay was hand-rolled into snakes and the snakes coiled one layer atop another. As the coils piled up they were pinched together, then scraped on the inside and out to smooth the surfaces, bond the coils together more and remove extra clay. In the paddle-and-anvil method a slab of clay would be laid over something already formed and it would be smoothed to that shape with the paddle. The Hohokam people were the primary users of the paddle-and-anvil method but they also used the hand-coil method to make the upper portions of their pots once they'd removed the "anvil" (the anvil was most often the bottom part of a gourd shell). Most Pueblo and Hopi potters used a basket bottom, a broken piece of pottery or a puki to shape and hold a slab of clay to use as a base to begin their coiling on.

This part of the process is shared in common by virtually all potters who do not use a potter's wheel or a mechanically-produced mold. Where elements differ is in the nature of the local clay itself and in how the potter might be intending to decorate the pot. Archaeologists have used mineralogical and chemical testing to analyze the unique and distinctive properties of the clay and temper used in ancient pottery in order to identify the location where a piece was made and its approximate age.

Colors: White, gray, brown, red, orange, black (although I'm only aware of a natural black clay occurring in Oaxaca, in southern Mexico). Color is mainly determined by the amount of iron and/or other minerals present in the soil. Different locations yield clays with distinct characteristics and colors. All aspects of the creation of the pot were made with clay which was easily available. Early Southwest potters often worked with more than one color of clay. Decoration was applied by brushing darker or lighter colors - red, black and white, over the surface. Sometimes designs were painted directly onto the dried formed clay body. At other times a slip, made from a different color of clay, was washed over the entire surface and allowed to dry before the design was applied.

The properties of the local clay determine the nature of a pueblo's pottery. San Ildefonso, Santa Clara and Jemez have clay bodies that are relatively easily polished, carved, painted and scratched. Taos, Picuris, Nambé and the Jicarilla Apache have micaceous clay bodies (although, for today's art market, most micaceous clay is applied as a slip over a buff clay body). Nambé potters have been allowed to share those micaceous clay sources. The Jicarilla Apache generally get their clay in the publicly-owned forests of northern New Mexico. Santa Ana, Santo Domingo/Kewa, Cochiti, San Felipe and Sandia have red body clays but most potters slip their dried pots with a whitish-yellow clay base before painting them. Isleta, Laguna and Acoma have white clays that are usually slipped smooth with white before being decorated with black, red and orange. Hopi and Mata Ortiz have a variety of clays available, some that can be polished and some that are used as slips and paints. Some Diné potters burnish their pots, fire them, brush them with pine pitch and burnish them again. After firing (and before coating with pine pitch) some Diné potters also use acrylic paints to decorate sections of their pots.

Richard Zane Smith uses different colors of clay to make his tiny coils. He seems to get a lot of his clay (and other objects he adds to his pieces) in the floodplain of the Missouri River, but then he lives in northeast Kansas and the branch of Wyandot he is a member of doesn't have a reservation of their own.

Then there's Clarence Cruz of Ohkay Owingeh. Clarence taught ceramics classes at UNM in Albuquerque for many years before retiring and returning to the pueblo. He's told me he makes two kinds of pottery now: Potsuwi'i and utilitarian micaceous. Potsuwi'i requires a bit of micaceous clay for painting the rock art-like grooves in his pieces but his utilitarian micaceous pottery is micaceous through and through. It can be used similarly to any other modern cooking utensil, including cooking over an open fire or in a closed oven. Robert Vigil once told me of going on a clay-digging expedition with Clarence in the mountains west of the Rio Grande in northern New Mexico. Robert was looking for softer clay with a bit of mica in it. He said Clarence kept going to the rock, the hardest stuff he could find with a high concentration of mica. That's what he wanted for his solid micaceous pottery, where Robert only wanted to make a usable slip to coat his pieces with. For Robert, Clarence's clay was the hardest stuff he ever worked with. Clarence, on the other hand, required that to make truly usable utilitarian pottery (all that mica makes his pieces stronger, too).

In most cases, the final coloring and overall smoothness of the dried clay body is the background on which the decorations are applied. Also, in most cases, the color of any decoration, as applied, is usually quite different from the color that decoration becomes once the piece is fired.

Sgraffito is an art process that often occurs after the pot is fired and the surface color is set. And depending on the depth of any particular scratch, the color of the revealed clay body beneath may be different. Some potters reverse that and scratch the clay before the pot is fired. Fired in an oxydizing atmosphere, those colors shine through. If the pot is fired in a reduction atmosphere to be black, that blackening process extends into the clay of the carved and/or etched design, making everything black.