The Mimbres Culture

Possibly the most famous, best preserved and most accessible Mimbres Mogollon site:

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument

The Mimbres Culture was a local development of the general Mogollon Culture. "Mogollon Culture" is a loose term applied to any of the people who were living in the environs of the Mogollon Rim (and south into Chihuahua, Mexico) from about 200 BCE to the mid 1400s CE.

The Mogollon Rim extends from southwestern New Mexico northwestward to west of the Grand Canyon in Arizona. It marks the southern edge of the Colorado Plateau, a large block of land around the Four Corners area that was pushed up by geologic forces about 65 million years ago. In some areas, the difference in elevation between the edge of the Rim and the desert floor below is 2,000 feet.

The Mimbres people were centered around the Mimbres Valley in southern New Mexico. The Mimbres area includes the upper Gila and San Francisco River basins in southwestern New Mexico and southeastern Arizona. Over time, their culture also expanded eastward to the the valleys on the eastern side of the San Andres Mountains. The San Andres Mountains run north/south but the line is cut in a couple places by canyons on both sides of the ridge. Archaeologists have found the remains of Mimbres villages on both sides of at least two of those canyon systems, indicating there were once trade routes passing through.

While the Mogollon Culture spanned more than a thousand years, the Mimbres Culture seems to have spanned the time period between 825 and 1450 CE with the most developed phase being between 1000 and 1150 CE.

From about 825 to 1000 CE the Mimbres developed distinctive pithouse villages. Houses were generally rectangular with sharp corners, well-plastered walls and hardened floors. They averaged about 180 square feet in size. Subterranean kivas were well developed and often included ceremonial features like foot drums. Pottery was already well developed and included early forms of Mimbres black-on-white ("Boldface") designs, red-on-cream designs and textured plain wares. Archaeologists feel Mimbres pottery was a localized extension of earlier Cibola ceramics from north and west of the Gila Mountains (Reserve black-on-white and Cibola black-on-white).

Something happened around 900 CE that almost overnight caused the Mimbres to burn most ceremonial constructions in their villages in spectacular conflagrations. After that it appears their social and spiritual practices changed and ceremonial constructions evolved to be more above ground.

[From about 946 to 950 CE, a volcano on the present-day border of China and North Korea erupted. It sent massive amounts of ash into the atmosphere for several years, bringing on a volcanic winter scenario in parts of the northern hemisphere.]

The Mimbres Culture was a contemporary of the Chaco Culture to the north. Both built structures of stone but the Chacoans built up while the Mogollon built out. The Chacoans built round ceremonial structures below ground while the Mogollon built their square and rectangular ceremonial structures above ground. The Mimbres people also buried their dead under the floors of their homes and the Chaco people did not.

When it comes to the decorations on their pottery, both Mimbres and Chaco had a problem with colors that wouldn't survive the firing, or any utilitarian use afterwards. That was a primary characteristic of the Cibola wares archaeologists feel were the precursors of all Puebloan ceramics: black decorations on a smoothed white base. Cibola wares seem to have been produced primarily in the Chaco Canyon area and traded to virtually everyone else in the area. Black-on-white Cibola bowls have been found from east of the Rio Grande to Hohokam settlements in central Arizona, and from Mesa Verde in the north to the southern Jornada Mogollon.

A comparison test was run several years ago to test a theory concerning whether cross-hatching might be related to missing colors and how that might relate to each culture in a ceremonial way. The test assumed that Chacoan cross-hatching signified blue while Mimbres cross-hatching signified green. Then the researchers found samples of pottery from each culture that pictured the same imagery in relation to a section of cross-hatching. The researchers ran their searches and comparisons multiple times, using multiple variables and inputs. Chaco tended to be blue and masculine (Chaco was a male-dominant society) while Mimbres tended to be green and feminine (indicating a more female-dominant society). Together with the Hohokam, the three were the great cultures in the Southwest at the time. Over the years since, the three culture's creation stories have been mixed and intertwined but they vary directly with greater distance from their sources and many of the finer details are expressed differently in different pueblos. Until the Spanish Franciscan monks arrived, it appears the original sources of virtually all the innovations in Puebloan spirituality have emanated northward from Mesoamerica and the central Mexican Highlands.

A Mimbres bowl with a pair of fish,

and a fine line and geometric design

Illustration by Will Russell

The Mimbres Valley was cut by the Mimbres River which flowed south and southwest from the Gila Mountains until it sank into the desert sand not far away. The stream hasn't drained to anything that reaches the sea in thousands of years, if ever. Because of that fact, there have never been any fish in the Mimbres River. However, the fish is probably the single most painted design on all Mimbres pottery that has been found. And the fish always have at least four lower fins (like most modern avanyu of the Northern Rio Grande Pueblos).

The Mimbres people also made extensive use of "checkerboard" designs. Today, that design can indicate everything from kernels on an ear of corn to a planted corn field to a starry, cloudy or stormy sky. Many of today's potters in Mata Ortiz decorate their pottery with nothing but versions of cuadrillo (checkerboard) designs.

Fine line designs have been traced as far back as petroglyphs in Oregon done by an Archaic Paiute artist about 4,000 years ago. The design can also be seen across the Southwest in rock art of the Plateau-Pueblo tradition. The rock art across the Southwest changed almost overnight in the late 1200s, too, corresponding to the rise of the Katsina, Warrior and Sacred Clown societies. But that was well after the Mimbres people had left their valleys and pueblos. Classic Mimbres iconography was more reflective of Mesoamerican religious influences.

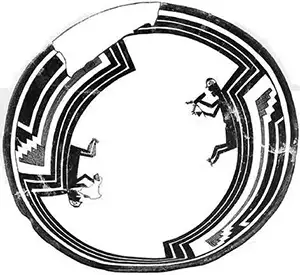

The right-handed Older Twin

being decapitated by the

left-handed Younger Twin

with a plumed serpent

on his back

Illustration by Kristina Wyckoff

The Classic Mimbres Phase lasted from about 1000 CE to about 1150 CE and was marked by ever larger stone masonry pueblo constructions with clusters of roomblocks (some containing as many as 150 rooms) centered around an open plaza. Quite often each roomblock had its own ceremonial rooms.

Kivas tended to be smaller and became square or rectangular in contrast to other Ancestral Puebloan circular designs. The largest Classical Mimbres sites are also located just above wide flood plains where regular water flows were able to support the level of agriculture they needed to support their population. There were smaller villages upland and downstream.

The Tularosa Phase lasted from about 1150 to about 1250 CE and is marked by the advent of cliff dwellings and the abandonment of the larger, less-defensible pueblo structures. By about 1250 most of the Mimbres Valley was abandoned with some people headed south and others north, east and west.

For many years it was thought the Mimbres simply disappeared but further research has turned up evidence that they migrated to nearby areas and merged into the local societies there. Some went north to the area west of Truth or Consequences, some to the alluvial fans on both sides of the San Andres Mountains, some to the Rio Salado area in eastern Arizona. Some groups then moved again, to Acoma, Laguna and Isleta while those in the Rio Salado area migrated to the areas of Zuni and Hopi. Some went south and merged into the cities and great houses of the Casas Grandes/Paquimé district in what is now northern Mexico.

The Twin Warriors

enjoying a smoke together

Illustration by Kristina Wyckoff

Most people associate "Mimbres" with Mimbres pottery, a highly developed and distinctive ceramic form. The pottery produced in the Mimbres region was often in the form of finely painted bowls, distinct in style and decorated with geometric designs and stylized depictions of animals, people and cultural icons in a black paint on a white background. These images often suggest familiarity and relationships with other cultures in northern and central Mexico. The elaborate decoration also indicates the people enjoyed a rich ceremonial life.

Early Mimbres black-on-white pottery, called Boldface Black-on-White (now called Mimbres Style I), is primarily characterized by bold geometric designs with a few early examples of stylized human and animal figures. Over the years, both geometric and figurative designs became increasingly sophisticated and diverse.

A bat with wings outstretched

and Venus (Morning Star)

symbols on its wings

Illustration by Will Russell

Classic Mimbres Black-on-White pottery (Style III) is characterized by elaborate geometric designs and very refined brushwork (including very fine linework). The pottery often included figures of one or more animals, humans, or other stylized images bounded by simple rim bands or by geometric decorations. Bird figures are prominent on Mimbres pots, including images of turkeys feeding on insects and birds being trapped in a garden. Images of fish are the most common, with illustrations from the stories of the Twin Warriors running a close second.

Toward the end of the Classic phase, the Mimbres potters found a way to add color to their designs. With color, they were able to add deeper meanings to their illustrations.

Should you learn a bit about Mimbres mythology, you'd see the designs all tell stories from their oral history. Many of those stories are still told among the Rio Grande Pueblos, many of those designs decorate pottery made today.

Mimbres bowls are often found in burial sites, usually with a spirit hole punched out in the center. Most commonly, Mimbres bowls have been found covering the face of a buried person. Wear marks found on the insides of the bowls show they were used in real life situations and not just produced as burial items.

Designs that were first painted on Mimbres pottery between 1000 and 1150 CE are still, today, being carved, painted and etched on pottery found in virtually every pueblo.

Lower images are courtesy of Kristina Wyckoff and Will Russell, from The Diffusion of Scarlet Macaws and Mesoamerican Motifs into the Mimbres Region