Sikyátki

The site of Sikyátki was first settled around 1200 CE by people migrating from the Hopi Buttes. At the Hopi Buttes they had been making Walnut Black-on-white pottery and they continued making it in their new village at Sikyátki. A few decades later, though, they relocated to the community of Old Walpi, a few miles away along the base of First Mesa, next to a better spring.

In the mid-1200s, a volcano in Indonesia blew its top and spewed ash clouds high into the atmosphere. Those ash clouds signaled the beginning of the Little Ice Age, a global, centuries-long weather pattern. The explosion of Mt. Sambalas enclosed the globe in clouds of thick ash for several years, dropping temperatures several degrees and destroying crops. The sun was not seen for several months, then the rains started. After the flooding rains came drought, the Great Drought of 1275-1298 CE. In that time span, the whole of Mesa Verde, the Tsegi Canyons, the lower Little Colorado and the Four Corners region were depopulated with families and clans migrating southwest, east and southeast. The 1300s were the time of the "Gathering of the Clans" that shaped a lot of modern Hopi society. Many small pueblos were built and then abandoned around the Hopi mesas, depending on how those migrants and their clans were received by the people already in the area. Those who seem to have been received with the most open arms were clans that began their journeys far to the south, some maybe from as far south as Paquimé.

In the late 1300s, people from a couple different Keres- and Towa-speaking pueblos located near Antelope Mesa relocated to the abandoned village of Sikyátki and expanded the size of the structures. Their occupation of the site is dated to have begun around 1375 CE, just before the major weather changes began again around 1400. By 1400, many of the pueblos on Antelope Mesa were being abandoned in the face of a major drought. Only Awatovi and Kawaika'a had nearby water sources sufficient enough to support them. The drought was a problem that reached far beyond the Colorado Plateau. Families, clans and villages were on the move nearly everywhere in the southwest.

Some of the incoming people were from the Salado culture, a group that had migrated south to the Upper Salt River Valley in the late 1200s. The Salado culture didn't merge into most of the indigenous societies they built near. The Salado people had a much deeper focus on spirituality and it reflected in the designs on their pottery. They also had new ceramic technology that made it easier for them to use local clays and minerals to make ceramics, wherever they might find them. They also pioneered painting designs directly on the polished clay body and not on a thin slip covering the clay body. By about 1450, the Salado pueblos were completely abandoned. Their clans were spread across southern Arizona but most seem to have migrated back to the Hopi mesas. About 1450 CE is the date given for the abandonment of the Little Colorado pueblos and the Mogollon pueblos, too. The Hohokam of southern Arizona also disappeared around 1450 CE. That is also the time when bands of Navajo and Apache settled into those areas recently depopulated by the Puebloans.

The almost immediate changeover in Hopiland was stark: the newcomers used Jeddito yellow clay and crushed mineral and vegetal paints to make their polychrome pottery, not the old bisque black-on-white. And their forms and decorations were significantly refined. Imagery from Katsina societies and sacred rituals proliferated. Defined Sikyátki-style pottery was produced from about 1400 to 1625, when the village was destroyed by other Hopis.

Sikyátki (meaning: Yellow House) was built next to a steady, reliable spring. The pueblo was constructed of the same yellow sandstone the mesas are made of. There are maps of the ruins but no drawings as to what the pueblo might have actually looked like in its heyday. From the size of the ruin mounds, J. Walter Fewkes felt it could have been four stories high with maybe 500 residents at its peak (by contrast, Awatovi was estimated to have been five stories high with as many as 800 residents at its peak). Sikyátki would have been just another ancient ruin in the Tusayan area except for some of the designs on the potsherds that litter the landscape.

The pueblo probably grew slowly in the beginning as families and clans moved from Antelope Mesa and built their places. There was an influx of people from the Homol'ovi and Casa Malpais areas around 1400 CE, then an influx of folks coming from Pottery Mound around 1450 CE. All of them contributed to Sikyátki becoming a bit of an artist colony (or perhaps a spiritual center).

That artist colony idea might have come from the Coyote clan. Today's Hopi Coyote clan claims descent from the Coyote clan of Sikyátki. The Coyote clan is charged with exploring ahead, picking out what's good for Hopi society, adapting that to Hopi society and continuing to forge ahead.

In this case, around 1400 someone at Kawaika'a maybe decided to make the journey to Pottery Mound to check out a new katsina ritual and art form that was developing there. They took part in that development and learned the ritual, costumes and designs that were part of it. Then they made the journey back to the Hopi mesas, bringing textiles and pottery imbued with the designs. Wall murals were painted with (what became known as) Sikyátki designs at Kawaika'a and Awatovi but not at Sikyátki. When some potters from Kawaika'a may have relocated to Sikyátki a few years later, they would have brought versions of those designs with them.

At Sikyátki, those new designs met and found a place among the older designs of the Kayenta, the Little Colorado, the Acoma, the Jemez, the Zuni and the Mogollon. An element that differentiated Sikyátki designs from other pueblo designs was the potters' affinity for creating three- and seven-panel patterns. Their designs also were imbued with an imbalance somewhere in their execution. Nampeyo faithfully reproduced and innovated some of those designs but shortly, most of her descendants were using the four-panel, fully balanced, design patterns of the ancient Payupki potters (Payupki design patterns were all the rage across the Hopi mesas from about 1680 to about 1780).

Sikyátki also became home to the Kokop (Firewood) clan, a recent transplant from the Towa-speaking pueblo of Kokopnyama on Antelope Mesa. The Kokop have been tied to a previous occupation of a round stone tower further to the east in Arizona, and their Towa language ties them to the Jemez people now in the Jemez Mountains of New Mexico. Recent speculation, fueled by research into ancient pottery designs and oral histories, has linked the Jemez people to the Fremont culture of northern and central Utah.

The potters of Sikyátki excelled at their craft and their products were traded everywhere from the Pacific coast to east of the Rio Grande, northern Mexico to the Great Salt Lake. It's extremely easy to identify pottery made in a Sikyátki form with Sikyátki decorations. Sikyátki set the bar for quality pottery with quality designs, until Payupki was built and populated. Payupki potters came really close but by the time they got started, Sikyátki had been destroyed more than 50 years previous.

There are a number of oral stories about the destruction of Sikyátki. All of them involve a problem with the people of Walpi (Walpi was the closest Hopi pueblo to Sikyátki, Walpi was built a couple miles away in the foothills below First Mesa and there were always water and farmland problems between the two pueblos). All the stories agree that the chief of Sikyátki approached the chief of Walpi and asked to have Walpi warriors destroy Sikyátki and its people for their wickedness. Arrangements were made and when the appointed day came (in 1625), virtually the entire village of Sikyátki was destroyed. Certain ritual specialists were spirited away early in the process and their clans were officially relocated to other pueblos (mostly to Walpi: the more clans a pueblo had, the more powerful and important the pueblo). Some of the women and young girls were spared, too, but everyone else was killed and the pueblo burned, never to be reoccupied.

Potsherds still littering the ground 270 years later attracted an Anglo trader named Thomas Varker Keam, his assistant Alexander M. Stephen, and a Hopi-Tewa woman named Nampeyo. Sikyátki might have remained just another ancient ruin at the foot of First Mesa, but Nampeyo was an excellent potter, so good that the first archaeologists to excavate at Sikyátki a few years later were afraid her work might be mistaken for the ancient pottery their workers were digging up. In the words of J. Walter Fewkes: "A careful examination of the beautiful productions of the prehistoric potters of Tusayan leads me to say that for fineness of ware, symmetry of form and beauty of artistic decoration the Sikyátki pottery is greatly superior to any which is made by modern Hopi potters."

Fewkes was the ethnologist who first dug into Sikyátki, in 1893. Financed by Mary Hemenway of Boston, Fewkes started exploring and digging in the upper reaches of the Little Colorado River in 1891 and 1892. He made the jump to the Hopi Mesas in 1893. That's when he began the dig at Sikyátki and started unearthing incredible ceramics. Then he crossed the line. He claimed that he introduced the Hopi-Tewa potters to Sikyátki styles and designs but, in reality, Nampeyo had been selling similar ware to Keam's Trading Post well before Fewkes arrived on the scene. And as much as she has been rightly credited with beginning the Sikyátki Revival phase of Hopi pottery, she also employed decorations that came from the ancient Kayenta, Little Colorado, Awatovi and Payupki pueblos. Some of those were a hundred or more miles away and abandoned before Sikyátki was born. At this point in time, those designs have been replicated so often, in so many places, in so many variations, it's hard to know their real source(s). And some elements are common to the vocabularies of most indigenous potters from one side of the continent to the other (like the universal "hand", the "spiral" and the "lightning bolt").

Sikyátki Polychrome Contemporaries:

- Early Sikyátki Polychrome is like Awatovi and Jeddito black-on-yellow with the addition of red outlines

- Bitahochi Polychrome has white outlines instead of red

- Kawaika'a Polychrome has massed white paint in addition to red

- Awatovi Polychrome is engraved through the black paint

- Matsaki Polychrome has thicker walls, a crackled buff or tan slip and ground sherds are used for temper. (Matsaki Polychrome was a contemporary Zuni product)

The site of Sikyátki is only a couple miles across the desert from today's Tewa Village. Many of the potters I've met who live near there walk regularly through the site, searching for inspiration and new designs. They walk around other ancient sites for the potsherds, too, and up and down the canyons for the rock art panels that are almost everywhere around the mesas.

The area of Awatovi sees almost as much visitor traffic for similar reasons. However, of the seven recognized ancient pueblos that line the Jeddito Valley and pre-date the arrival of the Diné, 5 of them are now within the Jeddito Island, a Navajo Nation property wholly surrounded by the Hopi Reservation. A Hopi guide can take you to Awatovi and give you a real introduction and education but I haven't heard of anyone except duly-papered archaeologists or folks local to Jeddito legally going for walks among any of the other sites there. I don't know that a Diné guide would be able to relate any of the real history of that area either. On neither reservation do you go anywhere off the public highways without a proper local guide close at hand, most especially around indications of ancient activity of any sort.

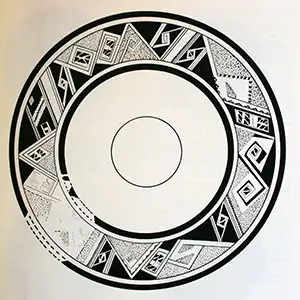

Design pattern is from Historic Hopi Ceramics

Sites of the Ancients and approximate dates of occupation:

Atsinna : 1275-1350

Awat'ovi : 1200-1701

Aztec : 1100-1275

Bandelier : 1200-1500

Betatakin : 1275-1300

Casa Malpais : 1260-1420

Chaco Canyon : 850-1145

Fourmile Ranch : 1276-1450

Giusewa : 1560-1680

Hawikuh : 1400-1680

Homol'ovi : 1100-1400

Hovenweep : 50-1350

Jeddito : 800-1700

Kawaika'a : 1375-1580

Kuaua : 325-1580

Mesa Verde : 600-1275

Montezuma Castle : 1200-1400

Payupki : 1680-1745

Poshuouingeh : 1375-1500

Pottery Mound : 1320-1550

Puyé : 1200-1580

Snaketown : 300 BCE-1050

Tonto Basin : 700-1450

Tuzigoot : 1125-1400

Wupatki/Wukoki : 500-1225

Wupatupqa : 1100-1250

Yucca House : 1100-1275